Dave Rust: Pioneeing outdoorsman and guide

A force behind making Utah’s desert famous

by William W. Slaughter

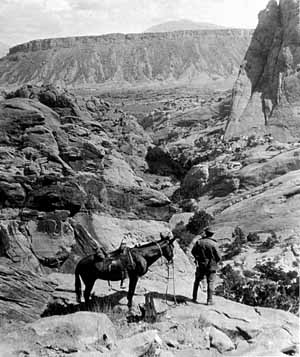

In July, 1925, residents of the Torrey-Teasdale area celebrated the scenic features of the Waterpocket Fold with a two-day festival. They hoped to attract more tourists and get a “Wayne Wonderland” state park established in the Fruita area. Their efforts led to the designation of Capitol Reef National Monument in 1937. Photo by Dave Rust; collection of Blanche Rust Rasmussen.

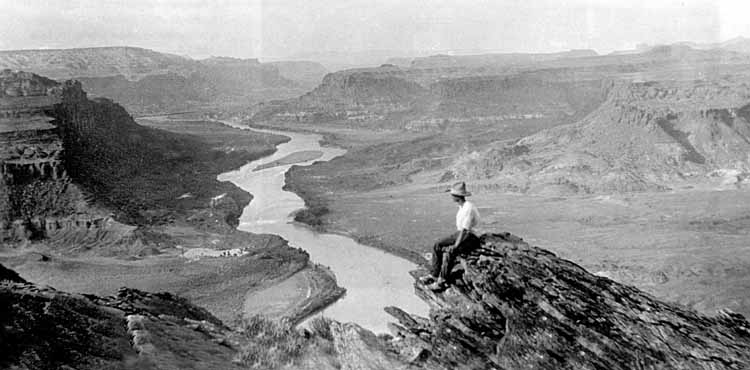

In 1914, standing next to the muddy Colorado River, David Dexter Rust pointed up at the walls rising hundreds of feet above Glen Canyon and declared to BYU educator Harrison R. Merrill: “This is a wonder river and a wonder canyon. Major Powell and Captain Dutton painted this country in words that will never die. People ought to see this country, t’s worth it, and by cripes, I’m going to help them see it.” These sentiments echoed his feelings for all of the southern Utah’s and northern Arizona’s wilderness.

Indeed, Rust spent some 33 years guiding parties in a quest to help them “see the wonders” of southern Utah’s unusual landscape. It is not a stretch to credit him, as interviewer Betty Brooke did, as the “man who helped make Grand Canyon a mecca for tourists, who guided people into Zion Canyon when there was only a faint trail, and who took parties down the Colorado before it was declared navigable.” He had a hand in building the first tramway across the Colorado River and stationing Phantom Ranch at the bottom of the rand Canyon. Among the many he guided down rivers, through canyons and over plateaus were Theodore Roosevelt, Zane Grey, riverman Bert Loper, mountain climber Leroy Jeffers and Utah Governor George Dern. His reputation was such that Harvar University insisted he lead the expeditions of the Peabody Museum. Of lifelong importance to him was his fortune to spend on the Bright Angel Trail with John Burroughs as they, in Dave Rust’s words, “discoursed like prophets.”

Born near Payson on March 10), 1874, and raised in Wayne and Sevier counties, Rust spent much of his boy-hood exploring the outback of Utah. However, as important as guiding and tramping were to him, David Rust exemplified balanced living. While he was, at various times, a cowboy a logger and a placer miner, he refused to be typecast. Interested in literature and writing, he majored in English at Brigham Young University and pursued graduate work at Stanford University. Dedicated to education, he taught school, was the principal of various schools, and served three terms as Kane County Superintendent of Schools. Incredibly, he rounded out his vita as a one-term mayor of Kanab, a newspaper publisher and a Utah state legislator On the side he wrote poetry and gardened – in 1917 he won $1,000 in a contest for the greatest yield of potatoes on one acre of ground; he raised 49,531 pounds per acre.

But throughout his varied life, Rust was devoted to “guiding folks” through his beloved wilderness. Prior to World War II, there were few guides in Utah, and “outdoor visitors” usually limited their visits to Utah’s national parks and monuments – much as they do today. Rust, however, offered the hearty and curious a chance to see much more. These trips were quite rigorous and covered a great deal of territory. A 1922 itinerary, for example, put Rust and his explorers on horseback for nearly 400 miles from June 29 through July 27. Their route started on the Aquarius plateau, with a stop in Teasdale, over Boulder Mountain to Escalante on down to the Paria River, east to the Wahweap to the Colorado River, and back to Escalante via the Kaiparowits Plateau. Yet. as strenuous as these trips were, his clients usually came back for more

Rust felt the ideal visitor to his wilderness “must be something of a geologist, something of a botanist, an archaeologist, an ornithologist, an artist, a philosopher, and so on. Through it all he is likely to be friendly with a camera. He must be agreeable in society, contented in solitude, enthusiastic and patient as a fisherman.” In other words, curious about life and adaptable.

Although not one to mollycoddle, Rust looked to the comfort and needs of his clients. And some clients could be quite specific about their “needs.” On New York Athletic Club stationery a “Major Gotshall” listed his needs for their upcoming “Colorado River and Hopi Expedition”:

-

1. Army cots on which to sleep.

- 2. Figs, dates, raisins, dried apricots and prunes, etc.

- 3 Raw carrots, potatoes, beets, turnips, etc.

- 4. Wheatworth whole wheat crackers and Ry-crisp.

- 5. Pancake flour

- 6. Bacon and ham.

- 7. Peanut butter

- 8. About ten pounds of shelled walnuts.

- 9. Large hunk of roasted beef to eat as cold roast beef

- Five gallons of honey Louse in place of sugar.

- l1. Goats milk if we can get it.

- 12. Swiss and other cheeses. Imported Swiss is the best.

- 13. A lot of whole wheat bread made with lots of raisins.

- 14. Nutty Fruit B read (I will send this to Mn Rust).

- 15. Whole Grain Wheat: whole ripe peas; whole navy beans; whole red kidney beans; whole lentils.

- 16. Some of the best California or other Olive oil.

- 17 Apples, Oranges, lemons, pears and any other fresh fruit we can get.

- 18. Skillets, pans, pots and other cooking utensils. Also tin cups and tin plates as selected by Mr. Rust.

- 19. Tents to use in case of rain. (Selected by ML Rust)

- 20. Some first aid material such as adhesive tape, absorbent cotton, bandages, iodine, etc., in case of accident

Rust does not record his reactions to this or other such lists. However, his reputation was one of accommodation and patience.

In later years, Rust recorded his thoughts about some of his tourist-clients. In 1909, writer- adventurer Zane Grey and Rust shared a Flagstaff hotel room. Amused, Rust remembered Grey “had a six-shooter under his pillow, a precaution altogether unnecessary at that late period in frontier history. He had come out west to hunt lions with Buffalo Jones on the Kaibab; purpose, to write stones for the market. An amateur author at that time, and decidedly green in saddling a mustang though a fancy shot with a rifle…. His first western romance, The Heritage of the Desert, is the literary trophy of the trip through the cow country bordering the Colorado.”

Out of this first outing with Grey, Rust became the model for a minor character in Heritage. In a January 2, 1911 letter, Grey reveals his respect for Rust as well as confirming his part in the book; “Of all the criticisms of my book [Heritage of the Desert], and I have received thousands, I like yours best. You can gamble that if the story stood the test you gave it, it has the stuff. I shall publish a few paragraphs of your lener, with your permission, and also that I drew the character of Dave Naab from Dave Rust.”

Theodore Roosevelt, Rust reminisced, “could focus on the chase in early morning become absorbed with the study of plants arid rocks and animals along the trail back to camp, make him- self at home while lunching cow-puncher fashion on the ground, linger at some choice lookoff for hours in the afternoon and thrill at the scenic masterpiece, assume the social leadership around the campfire… and sleep contentedly on a hard bed.”

The stern-looking, 6’1′, 175-pound Rust often intimidated dudes first meeting him. Most soon changed their minds. His love of life and the outdoors was infectious as he shared his knowledge of the history~ flora, fauna and geology of the region. A devout Mormon, Rust found wilderness a place of heightened reverence, and he willingly and gracefully shared his awe with his adven turers. They appreciated this strong, tough multifaceted man. Many, if not a majority, of his clientele were repeat customers. In fact, children of early-on customers continued to sign on for the Rust experience.” Such was the case with Theodore Roosevelt’s son Teddy. And long after their final western adventure, many people continued corresponding with Rust up until his death in 1963.

Frederick S. Dellenbaugh (a member of Powell’s 18~ -72 explorations) spoke for many when he wrote this simple but fine tribute about his longtime friend. “Rust… is a ‘corking’ fine fellow.”

Throughout his years of guiding, Rust hoped those who adventured with him would “love my country – Powell loved it; Dutton loved it; I love it, and so must you. I have failed if I fail to assist you to love my country. I count whatever money I may receive from any group of travelers as nothing… less than nothing, if they do not leave these breaks loving these gorges, these painted cliffs, and these dusty deserts!”